How the Wrong Questions Produce the Wrong Answers

“If I had 60 minutes to solve a problem … I would spend 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask, then I could solve the problem in less than 5 minutes.” – Albert Einstein

Socrates turned the way we learn upside-down. Prior to his revolutionary practice of asking probing questions to unlock insights, roving “Sophists” in Greece taught rhetoric – the ability to dazzle your audience with your knowledge in eloquent speeches.

Socrates saw that we learn nothing new by repeating what we already know, and that the audience retains very little of what is pushed at them. The power of questions is that they elicit participation in the learning process and hence ownership of the resulting insights. Socrates’ mother was a midwife and he saw her profession as a metaphor for his own method, explaining, “I don’t give birth to ideas, but I facilitate their delivery.” He approached questions with humility – without preconceived ideas, as a process of collective inquiry.

Everything we have learned through the ages came from a question someone asked. They are our “portals of discovery,” to paraphrase James Joyce. Yet somehow, we seem to have forgotten the power of pursuing good questions.

As a litigation lawyer in a prior career, I was drilled in the forensic art of asking the right questions in court battles. But it became clear to me in my current role as an educator that legal probes are exactly the opposite of learning questions. Litigation is adversarial. Questions in that forum are used as weapons. Learning questions are non-threatening invitations to explore the truth of an issue. No one is on trial. The key is to make it a collective endeavor, not a win/lose contest.

Many firms are striving to become “learning organizations.” But biases and entrenched thinking get in the way. Howard Gardner, the noted psychologist, calls these obstacles “engravings on the brain” that require “mental bulldozers” to clear them away. In a dynamic environment requiring constant re-assessment, cognitive bulldozers such as these are crucial.

The right questions can do this job for us. They force us to challenge our underlying assumptions, unfreeze our thinking and open our minds to new perspectives. The military calls this the process of arriving at “ground truth.” This is an art form, honed through practice.

Let’s examine how good questions can transform the understanding of a problem and change the course of events.

In 1776 the 13 independent colonies in America banded together in a war of independence against the British. George Washington was appointed to lead this disparate, poorly equipped army against the formidable British forces with their superior skills and greater resources.

Early in the conflict, the American rebel army was close to defeat. The situation looked grim. Washington engaged in an intense debate with his senior officers. “How can we defeat the British?” he asked. They spent hours agonizing over the possibilities from every angle but could find no good answer. It seemed like a depressing, game-ending conclusion.

But this debate ultimately gave birth to a transformative question that opened up a totally new way of thinking. Given the overwhelming odds they were facing, How will we defeat the enemy? turned out to be the wrong question. The right question that emerged was, How can we avoid losing? Based on this reframing of the challenge they devised an innovative strategy of surprise raids and quick withdrawals to avoid taking losses. It worked. They exhausted the British who eventually withdrew when the French provided the final push. It was the right question that saved the day.

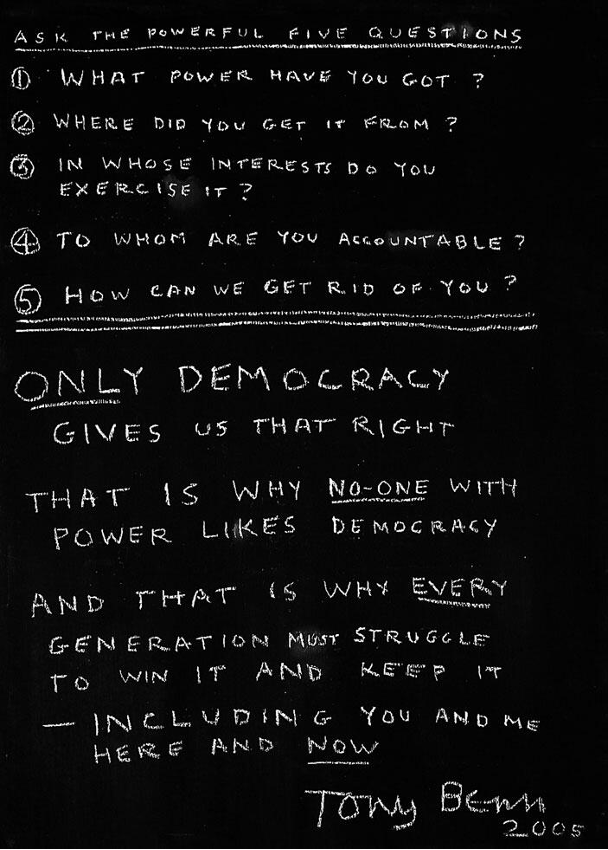

There is an ongoing debate about the essential features of a democracy. But how can we distill the hallmarks of an effective democracy in a memorable way? Tony Benn, a British politician, claimed there were five questions to ask people in power that revealed whether a true democracy existed. He often presented these insights to schoolchildren in the UK.

Depicted below is what he wrote on the blackboard in one of those classes. I don’t think there has ever been a better way to strip democracy down to its essence.

Benn argued that the last question is the most important one. In the absence of a consistently observed method for the peaceful transfer of power, democracy is in peril.

In the business world there has been an ongoing debate about stakeholder primacy. In the past, the view was that success was all about pleasing customers. This idea was gradually superseded by the philosophy that the overriding purpose of a business is to create shareholder value. Shareholders, after all, are the owners of the corporation, so the argument went. The latest volley in the debate came from The Business Roundtable which produced a statement declaring that the interests of all key stakeholders (such as customers, shareholders, suppliers, employees, society at large) should be served. Their rationale was that all these stakeholders are important. I suggest this misses the main point.

Sam Palmisano gave us the right way to think about this. When he was the CEO of IBM, he declared that in strategic discussions every IBM executive must have clear answers to the following four questions:

1) Why should customers choose to do business with us?

2) Why should investors choose to give us their money?

3) Why should employees choose to work in our company?

4) Why should communities in which we work welcome us in their midst?

Palmisano’s questions remind us that in a competitive world these stakeholders have choices. But the crucial insight is that if any one of these stakeholders is underserved, it undermines a firm’s ability to serve the best interests of the others. Try, for example, to generate shareholder value without pleasing your customers or with unhappy employees. It is not just that all these stakeholders are important – which they are. It is the mutual interdependence between them that provides the logic for the multi-stakeholder argument.

Sometimes a single penetrating question can improve a company’s competitive advantage. Starbucks’ mission statement states: We are not in the coffee business serving people. We are in the people business serving coffee. In the past, employees would call out the name of your drink when it was ready. In 2011 an enterprising barista pondered the question: what goes to the heart of being a people business? This simple question inspired him to write the names of customers on cups to personalize the experience. The idea was quickly adopted as standard practice and now happens 4 billion times a year at 30,000 locations worldwide.

Customer satisfaction is not just about product performance; it is also about how it makes people feel. Market research is not enough. Companies need to develop empathy – seeing the world through the eyes of the customer. As with the Starbucks example, asking thoughtful questions can make the difference.

Jacob Jensen was for many years the product designer for Bang and Olufsen’s home audio products. Jensen understood the need for a touch of magic in the design to delight the customer. Because of his work, B and O products are widely admired for both their performance and their beauty. Jensen pondered these four questions to help him design products with empathy:

1) Do you want to live with this equipment?

2) Does it make you happy when you see it?

3) When you touch it, can you sense that someone has understood how you communicate with this equipment?

4) Do you smile a little when you discover the heartbeat of the idea?

A powerful set of questions is employed by the US military in its famed After Action Review (AAR). The AAR is a rigorous inquiry conducted after every military engagement (simulated or real) to drive out lessons learned. This action-learning process focuses on four questions:

1) What was meant to happen?

2) What actually happened?

3) Why did it happen?

4) How can we do better in future?

The process focuses on learning, not blaming. The insights are sent to the Center for Army Lessons Learned (CALL), and then shared throughout the army’s ranks worldwide.

The US airline industry was inspired by the power of this method. After a series of fatal crashes in the mid-1990s, the FAA established a voluntary no-blame incident reporting system. The AAR method was applied to identify the root causes of every near-miss and crash, and the insights are now disseminated throughout the industry. Because of this learning system, flying actually becomes safer after every mishap. The results have been remarkable. For the past 13 years to the time of writing, US airlines have carried more than eight billion passengers without a fatal crash.

Good questions help us solve complex problems. But even more important is their generative capacity – enabling us to open our minds to ideas that didn’t exist before.

Socrates gave birth to a powerful new way of thinking 2,500 years ago, but his ideas have never been more timely. In this disruptive age, leaders need to heed his most important lesson: We will never have all the right answers, but we must have the right questions.

| Seven Important Questions We Seldom Ask 1) What assumptions must be true for this to be the right decision? 2) What will be the consequences of not taking this decision? 3) What are we aiming to achieve and how will we measure success? 4) What is the strongest counter-argument to taking this decision? 5) If we were not already in this business, would we enter it now? 6) What problem are we seeking to solve in the eyes of the customer? 7) What do we care about beyond making money? |