“Angels whisper to a man when he goes for a walk.”

– Raymond Inmon

As a CEO I developed a daily habit. Every morning before work, I walked for two miles through Central Park. My initial motivation was physical fitness, but I soon made a transformative discovery: During these walks, breakthrough ideas would come to me totally unbidden. Often, I found a solution to a knotty problem that had defied my attempts to produce a good answer through rational analysis or intensive discussions with colleagues.

I came to realize that these solo walks were not just a form of physical exercise — they induced a state of “mental freedom” that released avenues of creative thinking not evoked in conventional ways of problem solving. I protected my “walking time” zealously. On overseas trips, the rule was that my daily schedule would not begin until I had done my two-mile walk. Among my favorite places were the scenic botanical gardens in Sydney and the tranquil water gardens in Tokyo. Settings such as these intensified my awareness of our human connections to the natural world and opened my mind to even broader perspectives. Colleagues took to teasing me when I offered a fresh idea. “Ah, we see you took your walk this morning.”

What was going on here? At first, I thought this experience was idiosyncratic — an individual quirk. But the science tells a different story. Aerobic exercise such as walking improves our cognitive function by releasing two chemicals: A protein called BDNF that nourishes and energizes our neurons, and hormones known as endorphins that produce a sense of calm and well-being.

The combination of these chemical actions enables us to think in deeper, more imaginative ways. This is true for everyone. A Stanford study released in 2014 found that walking increased a person’s “creative output” by an average of 60 percent. Steve Jobs of Apple was known for conducting walking meetings, which are increasingly popular among employers, highlighted by a recent front page article of the Wall Street Journal that quoted an executive gushing how “ideas started to come to life” during a walk-and-talk through Bryant Park in midtown Manhattan.

Many of the world’s great thinkers got their breakthrough ideas while walking:

- James Watt, who perfected the steam engine that ushered in the Industrial Revolution, came upon his discovery while going “for a walk on a fine Sabbath afternoon. I was thinking upon the engine at the time and had gone as far as the Herd’s house when the idea came into my mind.”

- Nikola Tesla gave birth to the idea of the rotating magnetic field that enabled broad scale electrification during a walk in a Budapest park in 1882.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th century philosopher, produced his most profound thoughts during long Alpine walks. “All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking,” he claimed.

- Ludwig van Beethoven, the renowned composer, took long walks in the afternoons, regardless of the weather. He carried a pen and sheets of paper where he recorded his many inspirations during these outings.

- Werner Heisenberg, who discovered the foundations of quantum physics, achieved the breakthrough in his thinking during a two-week absence from the University of Göttingen to recover from an illness. He traveled alone to a remote archipelago on the North Sea and was doing nothing but taking daily walks and going for long swims when the bewildering intricacies of quantum theory formed clearly in his mind.

Today’s dynamic business environment presents us with a toxic mixture of speed and complexity. It is becoming nearly impossible with traditional thinking tools to make sense of these confusing conditions. We are being forced into shaping the future of our organizations on the run. We call hasty meetings, glance quickly at position papers, sit through dense PowerPoint presentations, and are then expected to make immediate decisions. I often hear the disturbing comment from executives that, “We don’t have time to do a strategy.” The challenge is clear: We must learn better cognitive skills to cope in real time with a disruptive landscape, in circumstances where we will never have perfect information.

There are essentially two modes of thinking: breaking an issue down into its component pieces (analysis) or seeing how the pieces fit together (synthesis). Research shows that strong analytical skills are common among executives, whereas the ability to synthesize is very rare. This presents a problem. Many major advancements in the history of knowledge, such as Einstein’s theory of relativity and Darwin’s insights on evolution, have been acts of synthesis rather than analysis. They involve seeing connections that had previously not been understood. While analysis deepens understanding, synthesis is a pathway to wisdom. By now, it should be no surprise to hear that Charles Darwin took regular walks. Einstein, while he was was grappling with the intricacies of his general theory, induced his mind to wander by playing Mozart on his violin.

As illustrated in the above examples, to walk is to think, and do so in different, more creative ways. In short, it helps us make sense out of chaos— a crucial role of strategic thinking. As the famous military strategist Carl von Clausewitz declared: What matters most is not what we have thought, but how we have thought it. I have found on my walks that most of my insights were acts of synthesis rather than analysis — perceiving patterns and finding meaning in the relationship between things.

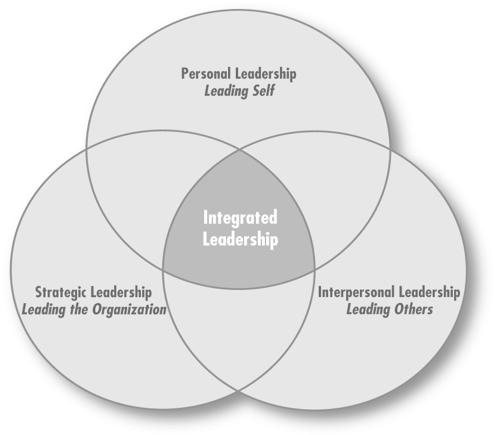

It was on one of my walks that I first discerned the idea of holistic leadership that unifies strategic leadership, personal leadership, and interpersonal leadership as depicted in the figure below. I began to see how these three domains are mutually supportive, like an ecosystem, and that if one aspect is deficient, it undermines the other two. This theory of integrated leadership has since found its way into my teaching. Would I have connected these dots while sitting at my desk? Maybe in rough outline at best, but it was the process of walking that sharpened and deepened my thinking.

The Three Domains of Leadership

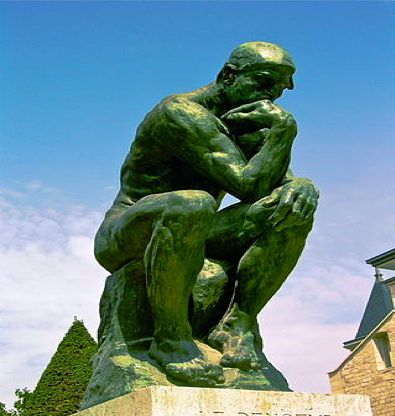

Two classical images sum up the contrasts in thinking methods. The first is Rodin’s “The Thinker.” It is an exquisite depiction of the male form in contemplation but sends absolutely the wrong message. A static posture is not the best way to develop creative ideas.

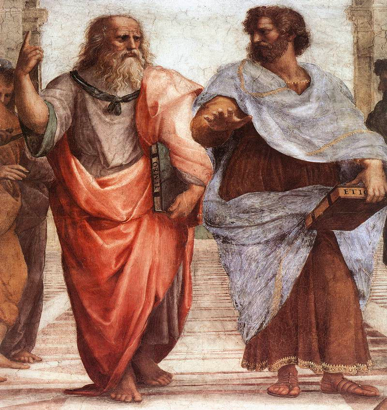

The second image shows Plato and Aristotle walking and reasoning together. This captures Aristotle’s unique practice of teaching while walking about. His followers became known as the peripatetics — Greek for strolling around.

Aristotle’s powerful example has come full circle. Modern times have created daunting challenges of thinking clearly in chaotic conditions while being assailed by constant distractions. Winning strategies depend on our ability to see through the fog of complexity and develop the keenest insights. We must sharpen our thinking tools. A simple and effective method is within our grasp. Become a peripatetic. In today’s parlance, take a hike.

Finally, a confession, and you probably guessed it: The idea for this story came to me during a morning walk.

Walking Tips

– Walk as a daily habit. Mornings are best.

– Venture outdoors (weather permitting) so you are exposed to the wider world.

– Turn off your cell phone.

– Ideally, walk for 20 to 30 minutes. Also take brief walks between intense mental tasks.

– Free up your mind. Ideas will come to you.

– Write down your insights and keep a learning journal.